Poets have long credited an unseen presence for the sudden line that arrives intact, the rhythm that “clicks,” or the image that won’t let go. That presence is often called the muse, a cultural shorthand for how creativity can feel both intensely personal and strangely external.

This article explains where the idea of the muse comes from, what it has meant in different eras, and how the muse of lyric poetry still shapes how writers and readers talk about inspiration today.

Origins: the Muses as memory, voice, and authority

In ancient Greek tradition, the Muses were nine divine figures associated with arts and learning. They were said to be daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory), a pairing that hints at an early insight: art depends on what a culture remembers and how it is performed aloud. Before widespread literacy, poets relied on trained memory, formulaic phrasing, and communal listening; “invoking” a Muse was a way to claim legitimacy for a public song.

Classical epics often open with a direct appeal for help in telling the story. That convention wasn’t only religious; it also worked like a declaration of method. The poet signals that the voice is part of a larger tradition and that the poem aims for something beyond private opinion. Even when the poem is personal, the invocation frames it as a craft guided by inherited forms.

Over time, the muses’ roles broadened, but the core idea remained: creative speech arrives through a relationship—between the poet and an enabling force, whether divine, cultural, or psychological. This is the early root of calling someone or something a muse of lyric poetry, because lyric depends on a speaking “I” that still wants to sound larger than one individual life.

Lyric poetry: intimacy, compression, and the need for a muse

Lyric poetry is typically shorter than epic and more compressed in meaning. It centers on a moment of feeling, perception, or argument, often using rhythm, sound, and figurative language to intensify experience. Where epic speaks for a community across generations, lyric frequently speaks from a specific body and situation—love, grief, awe, boredom, devotion, or doubt.

That intimacy creates a paradox. Lyric promises directness (“this is what I feel”), yet it relies on artifice: meter, line breaks, recurring motifs, and controlled ambiguity. The muse helps resolve the paradox by giving lyric a second source of authority. The poem is not merely a diary entry; it is shaped by an outside pressure—tradition, obsession, beloved person, landscape, or idea—that compels the speaker into form.

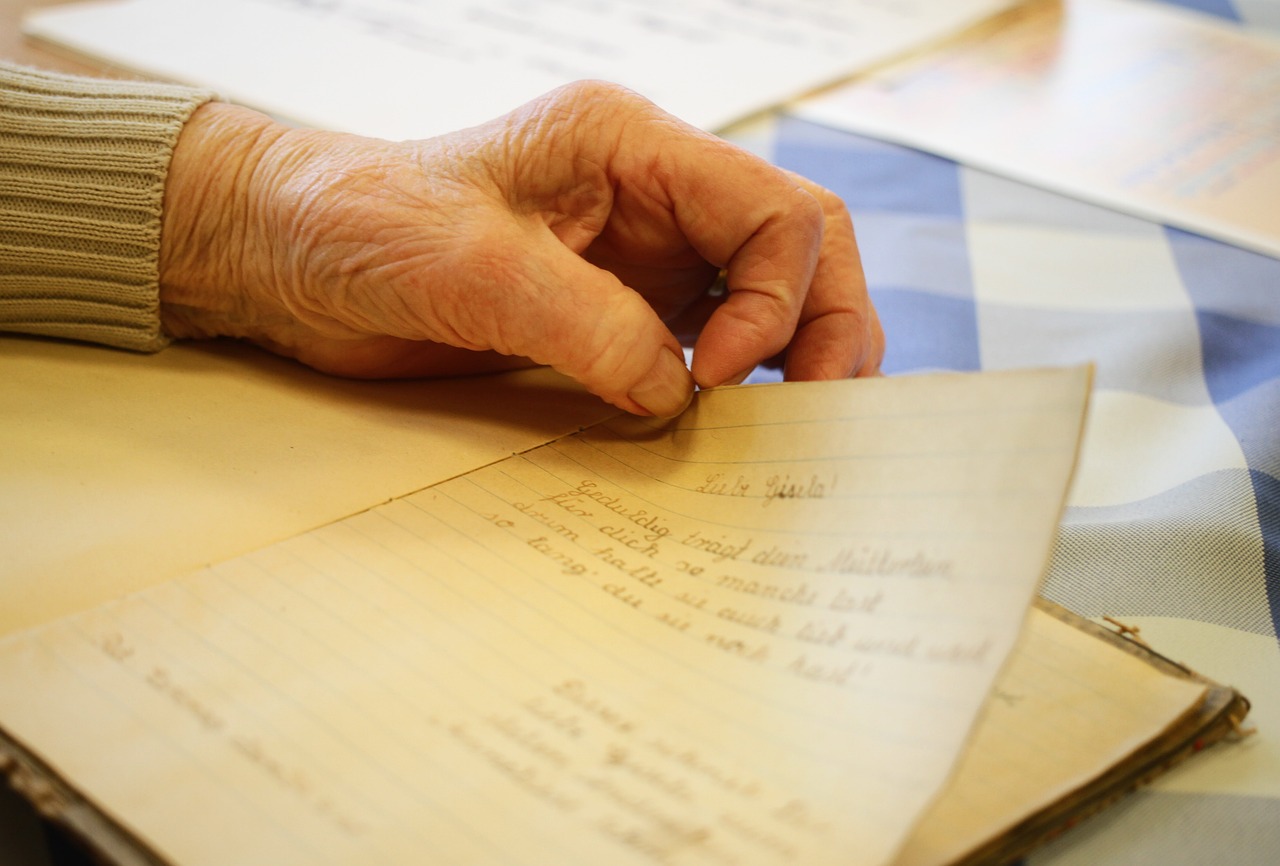

Historically, lyric muses have often been personified as a beloved. Petrarch’s poems to Laura set a lasting model in Europe: the beloved becomes an organizing principle for an entire sequence. Yet the muse here is not only a real person; it is also a poetic engine. The beloved is both subject and device, prompting repetition, variation, and refinement over many poems.

Modern meanings: from person to process (and the ethical questions)

In modern usage, “muse” can mean a partner, friend, city, era, or even a private obsession that sparks work. Psychology offers another lens: what used to be attributed to a Muse may resemble unconscious association, incubation, or the brain’s ability to recombine memories into new patterns after rest. Many writers describe alternating phases: long stretches of deliberate drafting, punctuated by abrupt leaps that feel “given.”

At the same time, the muse idea carries ethical baggage. When a muse is treated as a tool—a person reduced to inspiration—the term can excuse unequal relationships. The romantic myth of the genius and the sacrificed muse has often obscured the labor of collaborators, editors, and the muses themselves as creators. A balanced view recognizes that inspiration can be relational without turning anyone into an instrument.

Today, a practical way to keep the concept useful is to treat the muse as a set of conditions rather than a single figure: a reading habit, a daily walk, a conversation, a notebook of images, a musical rhythm, a constraint like a sonnet’s 14 lines. In that sense, the muse of lyric poetry is whatever reliably pushes the poet toward precise feeling and shaped sound—without pretending that the work writes itself.

Conclusion

The muse began as a sacred guarantee for sung poetry, evolved into a beloved or guiding spirit for lyric, and now often names the mix of influences and mental processes behind inspiration. However you define it, the muse of lyric poetry remains a useful metaphor for how intimate speech becomes art through pressure, pattern, and attention.